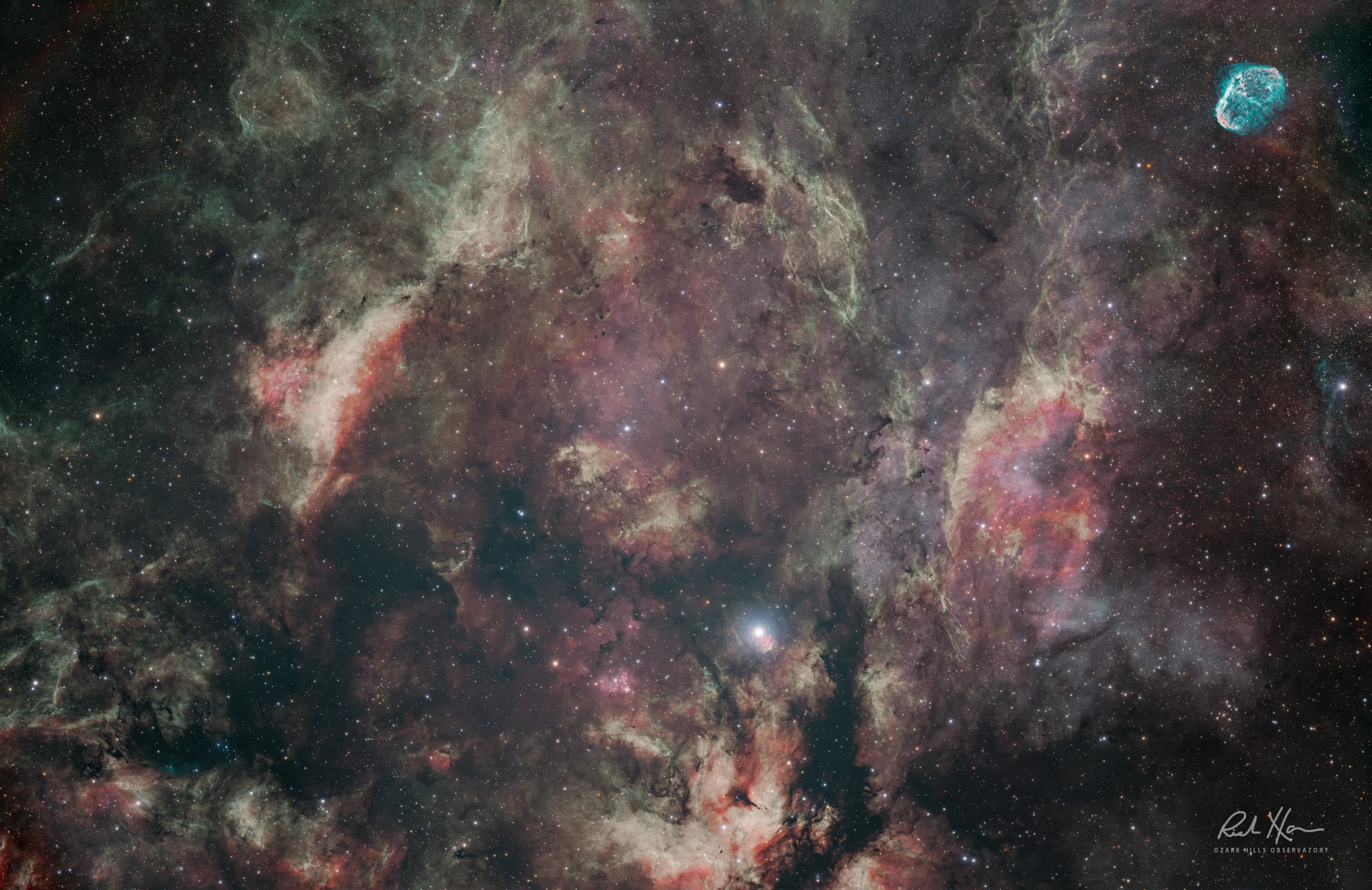

Trifid and Lagoon Nebulae

Trifid and Lagoon Nebulae captured together by amature astronomer Richard Harris at Ozark Hills Observatory using a 4" Takahashi telescope and 62 megapixel camera.

Happy 2026 everyone! There are nights when the sky feels less like a target list and more like a conversation. This widefield image of the Lagoon Nebula and the Trifid Nebula was captured with my four inch Takahashi FSQ 106 EDXIIII paired to a sixty two megapixel camera. It is a single frame view of a crowded and meaningful region of the Milky Way that I have been observing in one form or another for decades. Even after forty years at the eyepiece and behind a sensor, this part of the sky still asks new questions.

A Region That Rewards Patience

The Lagoon and Trifid sit in Sagittarius, looking inward toward the dense star fields of our galaxy. This is not empty space. It is a working neighborhood. Gas clouds, young stars, dust lanes, and energetic radiation all overlap here. A widefield view matters because these objects are not isolated. They belong to a larger structure shaped by gravity, radiation, and time. When you frame them together, the story becomes clearer.

The Lagoon Nebula

The Lagoon Nebula is a vast cloud of hydrogen gas where stars are actively forming. Its pink glow comes from ionized hydrogen excited by young hot stars buried within the cloud. Some of those stars are only a few million years old, which in cosmic terms means they just arrived. Dark lanes of dust cut through the nebula, not because something is missing, but because something dense is blocking the light behind it. Those dark regions are often where the next generation of stars will emerge.

The Trifid Nebula

Just above the Lagoon sits the Trifid Nebula, smaller but more complex. It earns its name from the dark dust lanes that divide it into three visible sections. What makes the Trifid especially interesting is that it shows multiple processes at once. Emission nebula glowing red, reflection nebula scattering blue light from nearby stars, and dark nebula absorbing light altogether. In one object, you can see several chapters of stellar evolution happening side by side.

Lagoon and Trifid Nebulea capture details

Astrophotographer: Richard Harris

Object: M8 Lagoon, and M20 Trifid Nebula

Date: June 25th - June 26th, 2025

Location: Strafford, Missouri USA

Telescope: Takahashi FSQ-106EDX4 with 0.7X 645 Reducer (380 mm)

Mount: ZWO AM5 harmonic drive

Camera: ZWO 6200 MM (monochrome), Temp= -20, Gain= 300 / Chroma RGB + SHO 3nm filters

Guide Scope: Williams Optics 50mm

Guider: ZWO ASI 290 mini

Controller: ZWO ASI Air

Narrowband Acquisition Details:

Sulfer II: 24 frames at 300s = 2 hours

Hydrogen Alpha: 24 frames at 300s = 2 hours

Oxygen III: 24 frames at 300s = 2 hours

Total acquisition time = 6 hours

Darks/Flats/Bias: (None)

Processing: Pixinsight, Photoshop

Bortle Class Sky: 3-4

Why a Widefield Matters

High resolution images are useful, but widefield images tell context. This field shows how these nebulae sit within a dense star forming corridor of the Milky Way. You see foreground stars, background stars, and everything in between. It reminds us that these famous objects are not special islands. They are part of a much larger system that we only understand in pieces.

Observation Over Certainty

I believe everything in the universe is evidence of creation. We cannot recreate a star or a galaxy to test our theories in the traditional sense. We observe what already exists and we build models to explain it. Physics, cosmology, and mathematics are tools we invented to help us make sense of what we see. They work well, but they are not complete. Our explanations change as our instruments improve and as our perspective evolves. That is not failure. It is humility enforced by scale.

A Personal Closing Thought

Astrophotography sits at the intersection of curiosity and restraint. You cannot rush the sky and you cannot bend it to your expectations. You collect photons that left their source before human history as we know it. You process them carefully, knowing that what you are seeing is an approximation shaped by distance, time, and limited vantage point. That awareness keeps the work honest. The Lagoon and Trifid remind me that discovery does not require certainty, only attention.

About the Author

Meet Richard Harris. He is the founder and editor-in-chief of ScopeTrader, with over 30 years of experience in observational astronomy and astrophotography. He serves as the director of the Ozark Hills Observatory, where his research and imagery have been featured in scientific textbooks, academic publications, and educational media. Among his theoretical contributions is a cosmological proposition known as The Harris Paradox, which explores deep-field observational symmetry and time-invariant structures in cosmic evolution. A committed citizen scientist, Harris is actively involved with the Springfield Astronomical Society, the Amateur Astronomers Association, the Astronomical League, and the International Dark-Sky Association. He is a strong advocate for reducing light pollution and enhancing public understanding of the cosmos. In 2001, Harris developed the German Equatorial HyperTune—a precision mechanical enhancement for equatorial telescope mounts that has since become a global standard among amateur and professional astronomers seeking improved tracking and imaging performance. Beyond the observatory, Harris is a serial entrepreneur and founder of several technology ventures, including Moonbeam® (a software company), App Developer Magazine (a leading industry publication for software developers), Chirp GPS (a widely used mobile tracking application), MarketByte, and other startups spanning software, mobile, and cloud-based technologies. Driven by both scientific curiosity and creative innovation, Harris continues to blend the frontiers of astronomy and technology, inspiring others to explore the universe and rethink the possibilities within it. When he's not taking photos of our universe, you can find him with family, playing guitar, or traveling.